One of my teaching tasks is the mentoring of small businesses here in the Portland metro area. Since I am “the Cash Man” the university has decided that I should guide local craft brewers in improving their cash flows. This is a fun assignment, but one thing I’ve now seen repeatedly is that it takes lots of cash to run a brewery: you need cash for the equipment, cash for the ingredients and materials, cash for tap room operations, and cash for people. As we’ve previously discussed, a business without sufficient cash is ultimately bankrupt. So, cash is king in every line of business, and in this case, brewers are typically either highly leveraged in debt or have an infusion of money from family members.

Craft brewers have some grand ideas. Some want to expand — literally — internationally. Others have product offerings of 20 to 30 beers in their tap rooms. The issue is that these businesses have neither the human resources nor the cash resources to execute on these ideas, and they don’t have a basic planning process to get there.

Back in January, I posed this question on this blog: How does a small business go about its planning?

Since then I’ve spoken with an old friend, Mr. Anne Bruggink, about this conundrum, and we continue to try and refine different ways to help. Like me, Anne has been mentoring small businesses (he in the U.K.,) and we agreed that most small businesses have neither the human resources nor the volume to allow them to operate the way that large multi-nationals do. Anne says that entrepreneurs tend to be too optimistic in some areas and too pessimistic in others. In my own experience working with small businesses, I’ve found that entrepreneurs are brilliant in areas such as product development, engineering, marketing and manufacturing, but can be left dazed when it comes to planning.

As I’ve studied the industry, I’ve found that the master brewers have pretty good control of the Supply side of the equation. Their response times are relatively quick, quality is good and they are generally aware of their production costs. Conversely, the Demand side of the equation is a much greater challenge. Do you sell entirely out of the tap room or should you use distributors? Should you take your product to other markets or geographies to increase demand? With little planning or availability of a cost-to-serve model, decisions are often made without regard to what will happen to cash and cash flow.

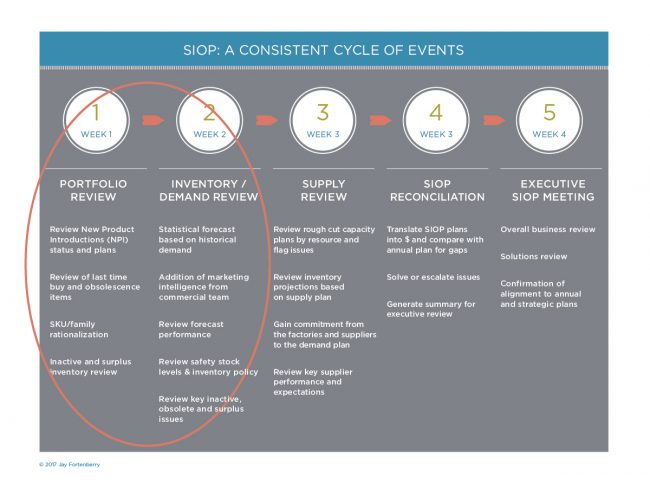

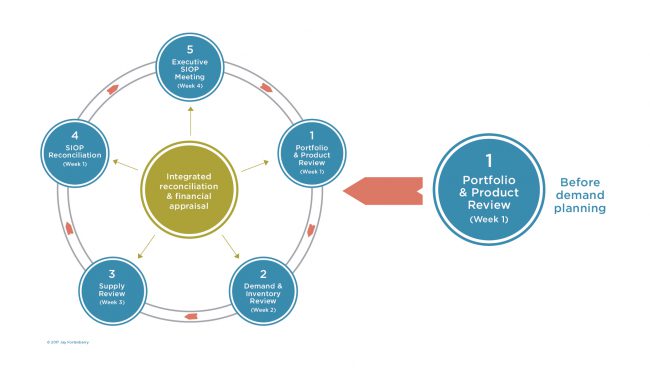

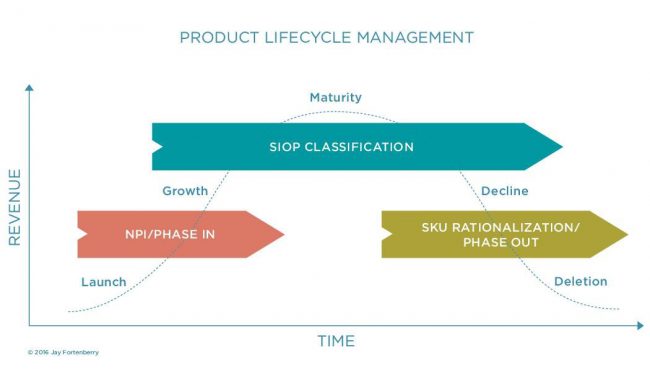

As a way of extending my experiences to small businesses that struggle with this, I will focus the next few weeks’ posts on the SIOP process, from Product Life Cycle management to Planning Demand, to Supply Planning and finally to include Sourcing.

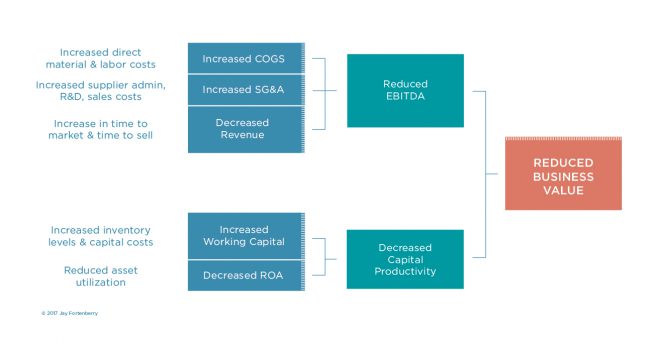

Every additional product line increases complexity from the design to delivery processes. Therefore, product portfolios can have an impact on performance and managing the portfolio of products (including the beginning of life, product rationalization and end of life) has a profound impact on working capital and operating cost.

What Does a Product Really Cost?

Factors to be considered in evaluating which products to make available are Cost, Sales and Margin. Listed below are just some of the costs related to delivering a product to the marketplace.

- Changeovers

- Schedule changes

- Component part management

- Tooling

- Maintenance

- Work in process inventory management

- Overhead for complexity

Logistics Costs:

- Warehousing and facility costs

- Inventory management

- Freight

- Overhead for complexity

- Supply management

- Materials management

- Design Engineering

- Developing and maintaining specs

- Testing

Sales and Marketing Costs:

- Training

- Communications

- Close outs

Customer:

- Warehouse/storage changes

- Display changes

Portfolio and Product Review

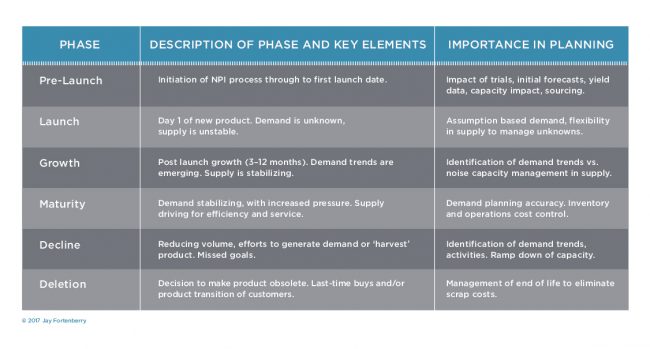

Product Portfolio Management aims to understand any changes to product offerings. The inputs are the product development pipeline, SKU rationalization and positioning, with a constant examination of the marketing channel strategy and the end-of-life for any product. Outputs are a volume- and dollar-based plan for any and all portfolio changes.

To effectively manage a business’s portfolio, focus needs to be on the following two areas, with planning different for each phase:

- The beginning of life

- The end of life

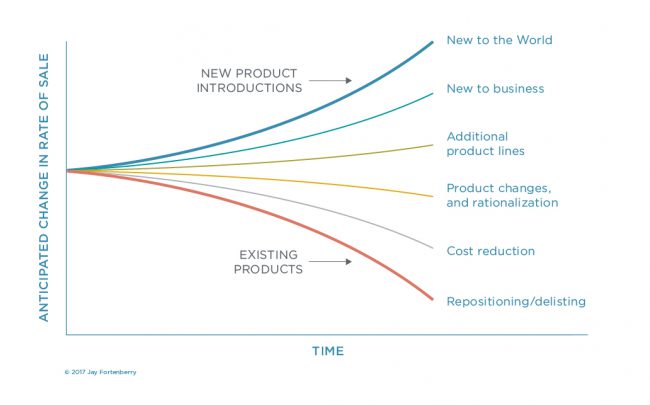

Additionally, a business needs to understand its sales profiles and how to support them. Different product strategies require different sales profiles.

The Beginning of Life Process

New Product Introduction

NPI has to have a complete end-to-end business view, not just one of engineering, sales or marketing. Assumptions need to be incorporated into the SIOP process with any changes tracked. Assumptions needed to create a forecast for the sale of a new product are:

Will it sell just like a product it is replacing?

If not replacing a product, what assumptions are needed?

- Market size

- Rate of market penetration

- Final saturation

- Replacement life cycle

You then need to determine how these assumptions are monitored and tested as the product rolls out.

A stage gate review process should be implemented, with the key functions participating being:

- Sales

- Marketing

- Engineering

- Finance

- Supply Chain

- Manufacturing

- Sourcing

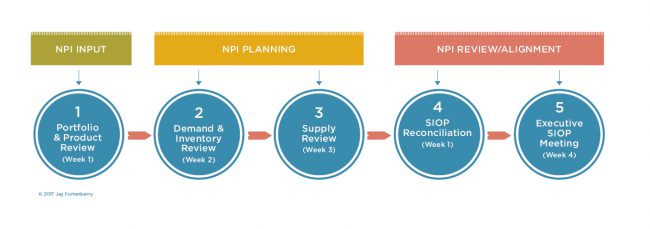

SIOP and NPI

NPI is a vital part of the SIOP Process. Demand planners need a view of all upcoming product introductions, including timings, volumes, probability of projects happening, assumptions to be understood and documented as well as identified opportunities and risks. Any changes should be recorded for incorporation into the demand review (schedule, volumes, risks, etc.). It is key to understand any significant changes as they happen.

Additionally, NPI with its phase in/phase-out of activities, plus product rationalization, are all vital parts of the portfolio review process.

Creation of demand profiles to support product launches, as well as a keen understanding of the launch and growth strategies, are again critical to managing working capital and operating expenses. For instance, is the business cannibalizing existing products or is this a new offering to the market? Will these products be Make to Stock or Make to Order, and what are the lead times and service levels anticipated by Marketing and/or Sales?

Product Rationalization

One way for a business to manage to the right level of complexity is through production rationalization as part of the portfolio review. This enables the business to:

- Optimize the portfolio for both top line growth and bottom line profit

- Identify lines of business that are trending towards non-profitability

- Identify lines that compete with each other (which can create channel conflicts)

- Create exit strategies targeted at controlling costs and potential customer disruption

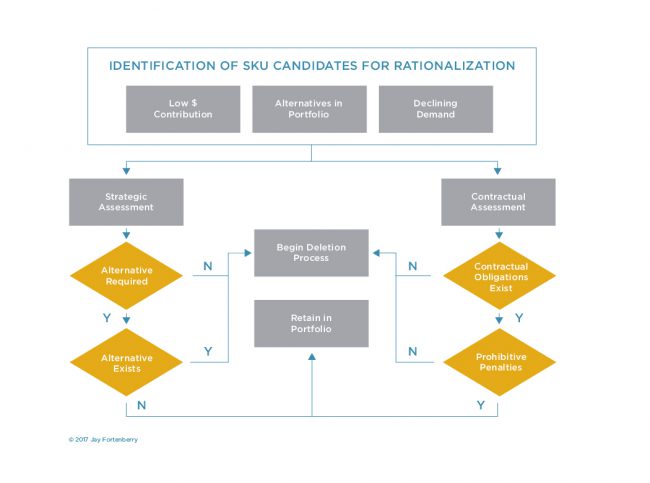

Simple SKU Rationalization Process

The handling of inactive, obsolete and surplus (IOS) inventories has a direct impact on working capital and requires aggressive actions to both reduce and prevent unnecessary inventory. Standard definitions for managing these types of inventories are:

- Inactive – no usage in last 12 months and no demand in next 12 months

- Obsolete – Items that are no longer in the product catalogue or any BOM

- Surplus – Inventory in excess of previous 24 months of sales

Activities designed to reduce or prevent IOS can include developing action plans and timelines to sell or dispose of material, as well as developing methods to predict slow-moving inventory and what will be excess in the next 3, 6, 12 months.

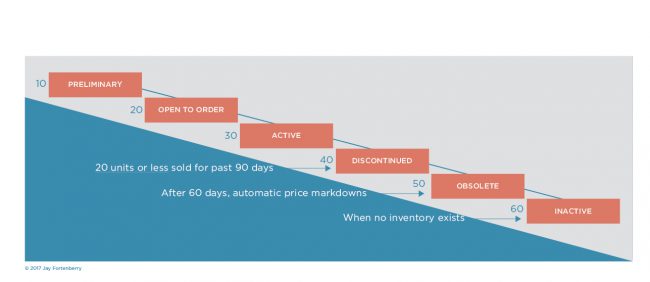

The End of Life Process

Working inside a Toyota plant for a model change to a Corolla or Tacoma was one of the most remarkable experiences of my career. The choreography was truly amazing to watch:

- A test line was fully laid out to build the new model, complete with machinery, parts and labor. We moved from a mindset of anticipating what would happen when we started to actually knowing and understanding where issues would be found.

- Concurrently, aggressive actions were being taken on the existing product lines and stores to manage down to the last part and determine how the last vehicle would be completed.

A great celebration was held throughout the plant as the last vehicle rolled off. It was amazing to see how we were left with only a handful of materials when the process was over, all of which were turned into service parts.

Most companies are able to create and maintain their product lines, but very few know how to kill a SKU or manage its end of life. Very few ask this question: How should we phase in the new product and phase out old ones? Not performing this task properly leads to SKU proliferation, as well as inactive, surplus and obsolete inventories. This is a waste of working capital.

Aside from a model change, ways to identify products for end of life are:

- A combination of low sales/ margins

- Determining if there are any strategic reasons for a product to stay

Ways to get rid of this material include:

- Discounts

- Scrap

- Donation

- Auctions

Managed properly, end of life helps a business clean up its inventories. Conversely, failing to manage can result in higher operating costs for holding the inventory, as well as increasing working capital requirements.

Final Thoughts on Portfolio Management

There are four critical elements to having a successful Portfolio Management process:

- A review the New Product Introduction (NPI) status and plans

- The review of last time buys and obsolescence items

- SKU and family rationalization

- Inactive, Obsolete and Surplus inventory review

A Disciplined Approach

I was once a new hire who inherited this process because no one else wanted it. I unwittingly accepted the additional workload from the intern returning to school (yes, they had an intern running Portfolio Management), and I knew New Product and End of Life from Toyota. At that point I didn’t realize that there was no process and that the data I’d been given was corrupt. Furthermore, after years of engineers building new product that there was no market for; inventory proliferated and financial targets were routinely missed.

Being a supply chain guy, I set a course and took the following steps:

- Ground myself with the academics of the process

- Stuck to my mantra of People, Process, Tools

- Developed a very rudimentary process for NPI and End of Life

Luckily, after six months of leading the process I was able to hire an expert in the area to step in, but I can affirm that it was hard and required massive amounts of communication across all of the functions.

For a small to medium business, this needn’t be a difficult or complex process. Simply sitting down monthly to review what’s selling and what’s not is all it takes. A business performing Portfolio Management properly can keep the reins on its cash, working capital and operating expenses in order to grow. Conversely, if this process is performed poorly a business can hemorrhage, draining valuable resources from other parts of the business.