Quality is a critical component of any manufacturing or service-related business: it has become the hallmark of most companies around the world. This emphasis got its start back in the 1920s, when S. Toyoda first invented an automated loom that stopped operations whenever a thread broke. It has now become the basic cost of entry into most marketplaces.

In Toyota’s case, emphasis on quality has had a dramatic impact on shaping both the brand and the way that the company operates. For those companies that don’t share the same priorities, poor quality can have a negative impact on cash flow. As was the case with Mr. Toyoda’s loom, you must never pass defects on to the next work station: when problems are detected, processes must be stopped and examined.

The 1980s brought a new awareness to consumers. They began demanding quality in their products, and in most cases they now receive it.

In my case, I’ve worked in both a TPS (Toyota Production System) and Six Sigma environment, as well as in a GMP (Good Manufacturing Practice) environment . I’ve personally always struggled with PPM as an accurate measurement. At both Toyota and the Nutraceutical1 up in BC where I worked,2 we measured down to the individual defect, working to prevent them rather than turning data into a meaningless aggregated number.

Last week I wrote about the Supply Chain of a Vitamin: when I was making pills, capsules, softgels and tablets, we literally made billions3 of these items. A typical run was one million, and I used to kid with the plant manager and finance lead that I finally understood PPM because that’s what they were literally doing! In this business’s case, a defect could have very serious consequences and would quickly drain large amounts of cash.

As I look back over 40 years of doing this and take everything into consideration, I stand for analyzing, understanding and reporting all exceptions.

Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP)

For my PPM friends, the Pharma and Nutraceutical industries live in a completely different world from ours. When you’re talking about humans ingesting your product there is absolutely no room for error: the data needs to be as perfect as possible. Granted, last week I talked about the supply chain data being nonexistent — but the quality data was readily accessible and good. This was a no-nonsense environment: exceptions had to be tracked down immediately.

It’s through this lens that I will try to describe a world-class process. Good Manufacturing Practices are essential to consumer safety. Through all of the studies we did, we never once questioned those aspects of the lead times and processes. Instead, our observations revolved around the amount of cash that it took to keep it all moving.

According to the International Society for Pharmaceutical Engineering (or ISPE):

GMP is a system for ensuring that products are consistently produced and controlled according to quality standards. It is designed to minimize the risks involved in any pharmaceutical production that cannot be eliminated through testing the final product.

GMP covers all aspects of production from the starting materials, premises and equipment to the training and personal hygiene of staff. Detailed, written procedures are essential for each process that could affect the quality of the finished product. There must be systems to provide documented proof that correct procedures are consistently followed at each step in the manufacturing process – every time a product is made.

These guidelines are global in nature and provide the minimum requirements that a pharmaceutical or food manufacturer must meet to ensure that products are of high quality; to meet labeling claims; and to not pose a risk to the consumer.

Good Manufacturing Practice guidelines provide guidance for the construction of the facility, sanitation, training, manufacturing, testing, and quality assurance. All of these have been set in place to ensure that a food or drug product is safe for human consumption. Many countries have legislated that food, pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturers follow GMP procedures: they are to create their own guidelines written to correspond with legislation.

Some of the guidelines that directly impact the Cash to Cash cycle and Cycle Time include:

- Manufacturing facilities must maintain a clean and hygienic manufacturing area.

- Environmental and equipment controls must be in place to prevent cross contamination of product.

- Production processes must be clearly defined, controlled, validated and audited.

- Operators are to be trained in GMP and SOPs, and training is to be documented.

- The distribution of food or drugs is controlled to minimize risk to quality.

- A system is fully operational and verified for recalling any batch with traceability to the raw ingredients.

Testing time for quality for raw materials and finished goods must be calculated into any customer commitment and cycle time process, ensuring that the spirit of the regulations are fully met. Additionally, managing the queue time into and out of Quality is critical to the proper flow of the process. Finally, appropriate care has to be taken during the shipping process so that factory fresh quality is delivered to the end user.

Toyota Production & Quality

I recently taught TPS to my undergrad students. TPS can be a challenge for most businesses, let alone for much-maligned millennials. My solution? I created what is probably the only version in the world of TPS BINGO to go along with the lecture. The game’s pieces were M&Ms — what they didn’t eat eventually filled up the cards. The goal was to help them understand this difficult subject. When we were done, I asked them if they now understood the subject of Toyota Production System. One of them perked up and said, “That’s just common sense stuff!” To which I replied, “You’re right!”

S. Shingo taught:

Defects generate waste and cause confusion in the production process.

He went on to teach that we must challenge ourselves to achieve zero defects. In his view this effort has three components:

- Inspections – the focus of inspections must shift from detection to prevention of defects. This requires a move from sampling to 100% inspection – the ultimate means of assuring quality assurance.

- Quality Control – must be based on the above approach, using such methods as source inspections, self-inspections and successive checks.

- Poka-yoke – a technique used for avoiding simple human error in the workplace. Also known as mistake-proofing or fool proofing, poka-yoke is a system designed to prevent inadvertent errors made by workers performing their process.

The lack of proper execution in quality can lead to devastating results. Product returns cost cash. Product recalls create bad will between companies and their customers. Worst of all, safety-related issues can impact the organization’s long-term viability. All three of these are a drain on cash flow, making it imperative that factory-fresh quality be delivered every time.

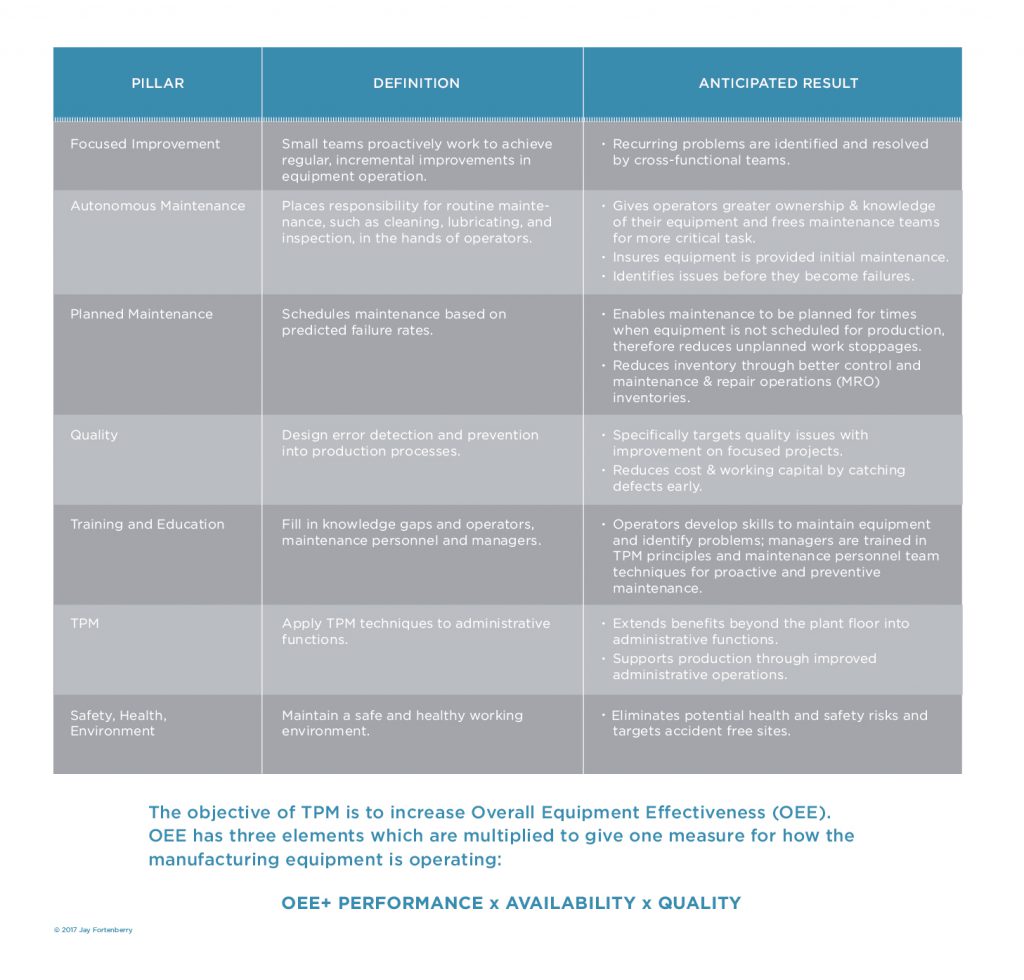

Manufacturing Maintenance Control – Total Productive Maintenance (TPM)

A few years back I worked with an Ops VP who used to say he wanted to Sweat the Assets. Now obviously, you want to use your assets to full capacity, but building in downtime is a must too. I saw this firsthand in BC while making those pills: failing to schedule maintenance properly can be devastating to the balance sheet and cash flow. You can miss an entire market and customer commitments by not building proper lead times in for downtime.

TPM was developed by Seiichi Nakajima to support Nippondenso’s Just-In-Time supply of parts to Toyota. This concept revolves around the theory:

You can’t be lean if you don’t have reliable equipment

The relentless pursuit of root-cause analysis and elimination of defects in the operation of manufacturing equipment takes total participation — from the leadership team to the shop floor. TPM is a philosophy of prevention based on autonomous maintenance, visual controls and a Kaizen (or continuous improvement) approach. It uses the goals of 5S to create a work environment that is clean and well-organized:

- Sorting – Discarding of items not needed in the work site

- Straightening – Orderly storage of all necessary items in dedicated locations

‘A place for everything and everything in its place’ - Sweeping – Clean all litter, trash and obstructions from the work site

- Sanitize – Clean or remove any unpleasant or undesirable item

- Sustain – Maintain and ensure a clean and organized worksite at all times

Three Elements of OEE

The objective of TPM is to increase Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE). OEE has three elements which are multiplied to give one measure for how the manufacturing equipment is operating:

OEE = Performance × Availability × Quality

Takes into account all events that stop production (typically several minutes).

Availability = Run Time ÷ Planned Production Time

Takes into account anything that causes the manufacturing process to run at less than the maximum possible speed when running.

Performance = (Optimal Cycle Time × Total Count) ÷ Run Time

Takes into account manufactured parts that do not meet quality standards, including rework. Similar to First Pass Yield, it defines good parts as parts that successfully pass the first time without needing any rework.

Quality = Good Count ÷ Total Count

Final Thought on Quality

Mistakes are costly – the lack of proper execution in quality can lead to devastating results, including:

- Product returns cost cash.

- Product recalls create bad will between companies and their customers.

- Worst of all, safety-related issues can impact the organization’s long-term viability.

All three of these are a drain on cash flow. Therefore, it is imperative that factory-fresh quality be delivered every time.

In my first exposure to manufacturing, I was parachuted into the Motomachi, Japan Toyota plant. Once there I was instructed to “do Kaizen.” In the eyes of my senseis, it didn’t matter that I was the only one there who spoke English or that this neophyte American was supposed to teach the masters of quality and continuous improvement how to improve their processes. I ended up observing, walking in their shoes, and discovering. I did review my suggestions with them, but it was a fascinating learning experience for me. This is how I developed the ability to quickly look at an operation and see how to enhance pieces of it without being disruptive to the entire process.

Thirty years later I’ve worked in a wide variety of plants, marshalling yards, warehouses, etc. As I said last time in my vitamin blog, making a softgel is really no different from building a car – it’s all the same relative process, whether what’s being built is hundreds of tractors, or millions of cars, or (most recently) billions of soft gels, capsules and tablets. It all comes down to capacity, labor, materials and your quality.

People are the same all over the world. We take pride in what we make and harbor a deep affinity for ensuring that a quality product is delivered to our customers. There are no silver bullets — just good old-fashioned rolling up your sleeves and getting the job done.

Building quality in from the start is the only path a business should take.