After I decided to leave the corporate world three summers ago, I started consulting with some colleagues in British Columbia.

Our client was a mid-sized manufacturer of vitamins and supplements. The owner prided himself on adhering to GMP (or Pharmaceutical standards) in his procurement, storage, quality, manufacturing and distribution processes.

Our client was a mid-sized manufacturer of vitamins and supplements. The owner prided himself on adhering to GMP (or Pharmaceutical standards) in his procurement, storage, quality, manufacturing and distribution processes.

This entrepreneur grew his own Ignatius flowers for some of his products. He also dealt directly with fisheries in Alaska for fish oils. It was an amazing supply chain to map. The process required being able to bring thousands of ingredients from all over the world to Vancouver, BC, where they would manufacture literally billions of pills, capsules and softgels and then distribute them all over the world.

After learning how to make a soft gel I determined that making a vitamin was really no different from making a car, truck, tractor or thermostat. There’s an old saying that goes, “Parts are parts.” In this case that was exactly right: parts were parts. Mostly the manufacturing ran well. They totally lived up to GMP standards while producing billions of items. The problem was that there was no credible planning process and weak supplier communications with multiple signals (push out/ pull in’s) per day. It was a true mess, and I don’t think anyone had looked closely at the supply chain in decades. This monster had grown tentacles all over the world, and unwinding them would take a concerted effort.

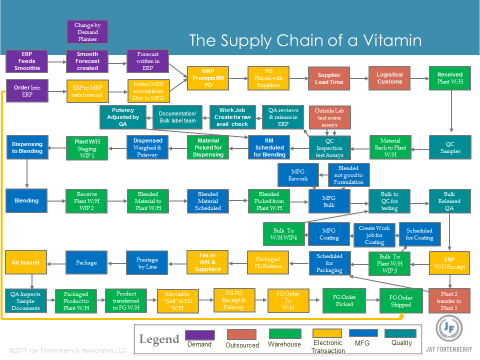

Mapping the Supply Chain of a Vitamin

Controlling the supply chain came down to the basics: supply management, logistics, a credible planning process and my personal favorite … good old MRP accuracy. We couldn’t (and didn’t) want to boil the ocean (so to speak), so instead it became my quest to map the process. I stapled myself to an order and followed those little pills, capsules and softgels all over the place, bouncing around Vancouver, British Columbia like a pill falling on the floor.

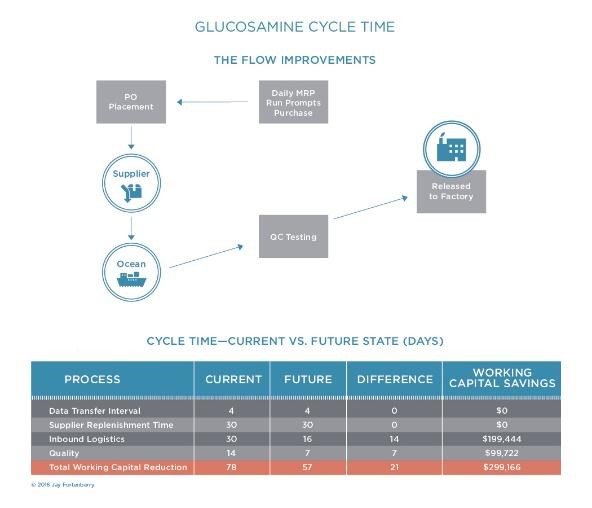

From here, my colleague Ed Lawton was able to provide numbers. We got the spend, usage and inventory numbers for raw materials and it was a gold mine for us. Together we followed the data to come up with a case study for raw materials. For supply we chose the ingredient Glucosamine, but it could have been any of the manufacturer’s products, as they all followed a similar path.

Since Glucosamine was one of the largest ingredients, our hypothesis was that if we could get that under control with a repeatable process, we might be able to stabilize the rest.

Since Glucosamine was one of the largest ingredients, our hypothesis was that if we could get that under control with a repeatable process, we might be able to stabilize the rest.

By methodically walking our way through the different systems, sourcing strategies and logistics we were able to simplify the process by developing a plan that eliminated three weeks of waste. Additionally, these improvements enabled a greater level of scheduling for both QC/QA and manufacturing. This translated into a higher rate of customer satisfaction while reducing working capital by $300,000.

A Process Ohno Would Be Proud Of

Within six months Ed and I were able to build a simple, repeatable process. The client could methodically move through their individual pain points until they ran out of problems. At the same time we were able to develop a Kanban process for the high runners, like capsules. As Ed and I continued to work through the supply chain, the client began to hire very competent leaders to take over from us. This meant that we were able to hand off these projects for someone else to manage. The moral of this story was that things were repeatable, millions of times a day. Ohno would have been in heaven.

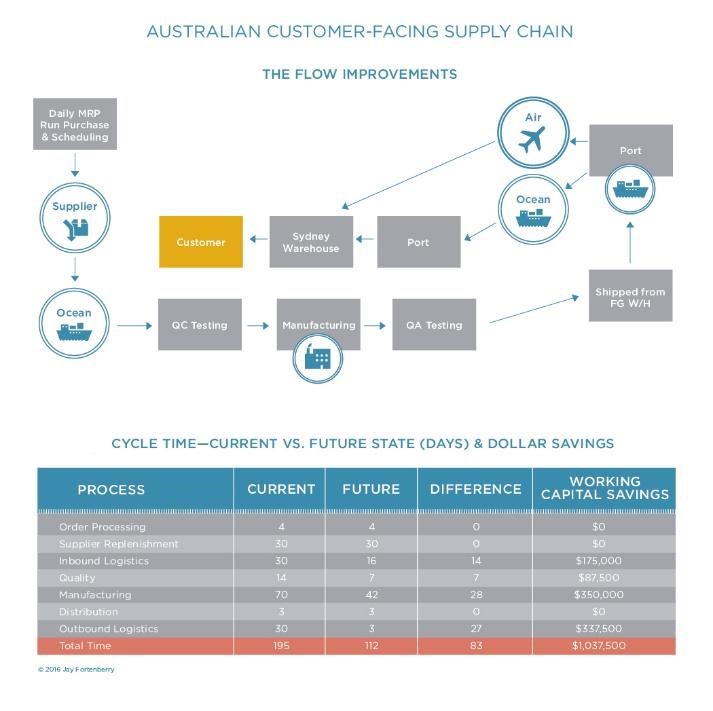

For Finished Goods we chose the movement of finished goods to Australia. In this case the supply chain was fraught with fines and penalties, order management problems, lead time violations, inventory management issues and simply long lead times from BC to Sydney. It was a real mess, with a negative ROI. It was a classic case of pitching your distribution over the transom and totally losing control of your business model, literally on the other side of the planet. The bleeding was immense, with no end in sight, and this was indicative of all their export orders.

For Finished Goods we chose the movement of finished goods to Australia. In this case the supply chain was fraught with fines and penalties, order management problems, lead time violations, inventory management issues and simply long lead times from BC to Sydney. It was a real mess, with a negative ROI. It was a classic case of pitching your distribution over the transom and totally losing control of your business model, literally on the other side of the planet. The bleeding was immense, with no end in sight, and this was indicative of all their export orders.

By analyzing the way they went to market we were able to make significant changes that reduced working capital by over $1 million, while improving delivery, quality and expiry. This quick hit improved cash flow, which immediately went to the bottom line.

My Conclusion

This project took me about a week to figure out. Once again I stapled myself to an order. This time I could actually follow things from the work we had already done on supply. Also, I was able to talk to everyone who’d been associated with the process over the previous 5 years, so problem diagnosis and solving was much easier.

I do want to acknowledge and thank the clients’ Quality department for teaching me GMP. Operating under GMP is a much different world from PPM. Good Manufacturing Practices are essential to consumer safety. Through all of our studies we never questioned those aspects of the lead times and processes. Instead, our observations revolved around the amount of cash and working capital it took to keep it all moving.

Double digit productivity can be achieved through a careful mapping of the supply chain, all without investing in additional people or expensive systems.

By walking through the supply chain from order to delivery, we learned:

- How customer orders were received, processed, scheduled, and shipped

- Where value was added and where it was taken away

- How lead times, inventory and transportation impacted working capital

- How New Product Introductions (NPI) impacted cash flow

- Where the opportunities for rapid improvements existed

Final Notes

As a quick closing note, the company’s MRP operated just as it had been programmed. The trouble was that bad data destroyed every plan. I cringed as we went through this process, but it was necessary to clean things up in order to make them sustainable. We analyzed 18 months of data to come up with solutions that provided real, immediate and sustained cash savings.

Cool stuff: Ed and I knowing how to unlock the vault meant the client was able to get to their cash.

This five-minute video will give you more information on how we achieved double-digit improvements in productivity. At the same time, we increased their bottom line.