Keep Cars Moving, Maintain Quality, Promote Efficiency

A little context to the story

Two weeks ago I was wrapping up my Intro to Supply Chain course at Portland State University. The subject of the Toyota Production System (TPS) came up, so I went back to the many presentations I’d collected over the years and took the class to see the Toyota operation at the Port of Portland. It was there, 35 years ago while working for Union Pacific, that I first experienced the world of Toyota.

Terminal 4 in Portland was my home. It was back in the days of the go-go 80’s – a supercharged time before Toyota’s North American automobile production, when a ship would come in, discharge thousands of new cars, and leave. We’d then move unit trains east until the vehicles were gone – working weekdays, weekends, or holidays. All that mattered was moving cars. When we were done, we’d get ready for the next onslaught, then start all over again.

Years later, on a cold and rainy day in March, a Toyota Vice President with a reputation bordering on madness came to Portland to discuss quality issues that Union Pacific was causing. Somehow, all of my bosses managed to be somewhere else, leaving me to take the brunt of this man’s anger. The butt-chewing went on for hours, but strangely enough, I would later be recruited to work for this wild man – and that is where my journey inside the world of Toyota really started.

I was sent to Japan, where I was incredibly lucky to observe and learn from the old masters who started the company. It was intellectually stimulating, and as it turned out this was where I developed the core beliefs and principles I hold to this day.

I would learn my lessons and then be jettisoned to the factory floor or to a marshalling yard to do ‘Kaizen’. It didn’t matter that I was a newbie, or that I couldn’t speak a lick of Japanese and barely understood the concepts of Kanban, Heijunka or Jidoka. I was to do Kaizen. I followed my teacher’s’ instructions and ultimately found my niche inside this new world.

All of the lessons learned shaped me and my fellow students into solid operations managers. We had so many great teachers, a fact for which I’ve always been grateful. We had the opportunity and privilege to learn from such noted dignitaries as E. Toyoda, Ohno, Deming, Imai – and soaked up all their wisdom and knowledge. At the same time, I had the opportunity to work for Gary Convis and Bob Bennett, learning how to build a car under Gary and the concept of Servant Leader from Bob.

Until this past week and our visit to the port, I hadn’t realized how much I missed those days. In tribute, the following is my understanding of TPS.

Background

Kiichiro Toyoda established the company that would later become Toyota Motor Corporation. During his tenure he nurtured the processes of Just in Time that would become one of the main pillars of TPS. In the early 50s. E. Toyoda visited Ford Motor. He decided to adopt the American method of mass automobile production, but with a qualitative difference.

E. Toyoda collaborated with Taiichi Ohno, a veteran loom machinist. During one of Ohno’s visits to the U.S. he had discovered the American supermarket. He admired the way that customers could choose exactly what they wanted, in the quantity they wanted, and when they wanted. He studied the simple, efficient and repeatable manner in which stores replenished their inventories. These firsthand experiences would assist in the development of the core concepts of Kanban, and other processes to cut costs while improving overall quality.

During this same time period, Dr. Edwards Deming was brought to Japan to work on improving quality. Deming trained hundreds of engineers, managers, and scholars in statistical process control (SPC) and other core concepts of quality. The observations below became Deming’s 14 Points, as outlined in his book Out of the Crisis.

- Create constancy of purpose for improving products and services

- Adopt the new philosophy

- Cease dependence on mass inspection to achieve quality

- End the practice of awarding business on price alone

- Improve constantly every process for planning, production and service

- Institute training

- Institute leadership

- Drive out fear

- Break down barriers between staff areas

- Eliminate slogans, exhortations and targets for the workforce

- Eliminate numerical quotas

- Remove barriers to pride of workmanship

- Institute a vigorous program of education and self-improvement for everyone

- Put everybody in the company to work accomplishing the transformation

Together, this all became the bedrock of what we know today as the Toyota Production System.

What is the Basis of Toyota Production System?

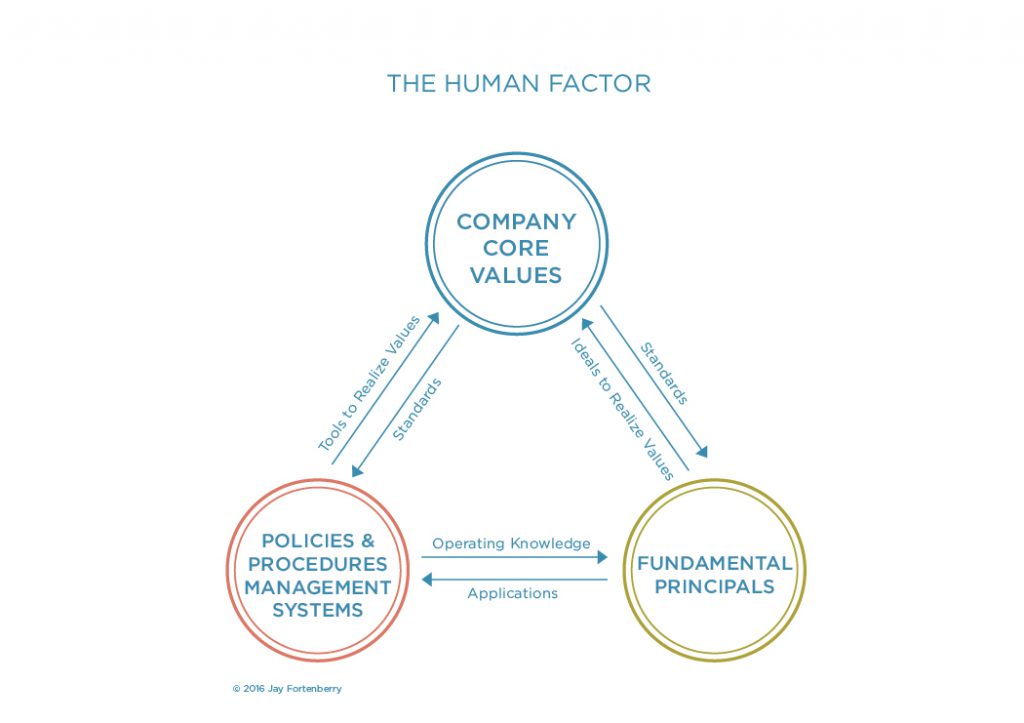

People

On the first day of work at Toyota we learned: A business is not just a ‘for-profit’ enterprise. It also bears a social responsibility to its customers, to its employees, and to the community to make quality products at reasonable prices. It is not just a company’s facilities, machines and capital that build products, but also its associates who actually perform the work. We went on to learn:

“As a business enterprise, it is important for Toyota to keep a good balance among the company’s values and consistently apply those values in all its systems and policies.”

- Customer first

- Competition and cooperation within the industry

- Respect for the value of people

- Mutual trust between employees and management

- Challenge and courage

- Applied creativity

- Cost consciousness

Further, we were taught that our fundamental principles were:

- Consider the mid/long-term needs and inputs

- Genchi Genbutsu, or seeing is believing

- Seek the most rational way

- Strive for cost efficiencies

- Promote teamwork

- Develop your people

Everyone from the boardroom to the assembly line understood and applied these principles. This message was stressed and reinforced daily along with the importance of keeping a proper balance so that these standards were equally applied in all circumstances.

The Processes

TPS is about the complete elimination of Muda. Muda is unnecessary waste that adds no value, increases cost and lead times while deteriorating quality. There are 7 kinds of waste:

- Waste from over producing

- Waste from waiting

- Waste from conveyance

- Waste from improper processing

- Waste from inventory

- Waste from non-productive motion

- Waste from producing defective product

If you understand that selling price is dictated by the market, then in order to increase profitability Muda must be minimized and eliminated. It is from this premise that all of the key success factors of Toyota Production originated.

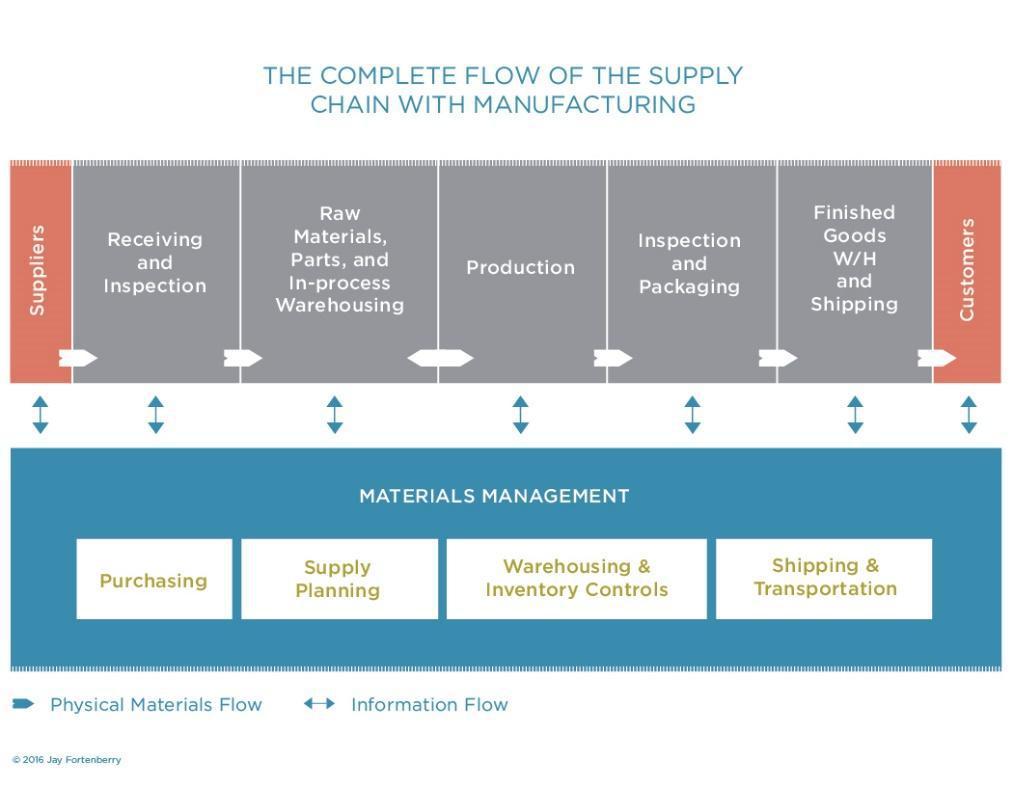

Just in Time

“If you produce only the necessary products at the necessary time and in the necessary quantity, waste, irregularity and the unreasonable disappear and the improvement of productivity becomes possible.”

Taiichi Ohno

The primary goal of Just In Time production is to translate each order into the delivery of a finished vehicle as quickly and efficiently as possible with factory fresh quality. This is accomplished through the basic principles of:

- Pull Systems – withdrawing parts when they are needed, in the necessary quantity

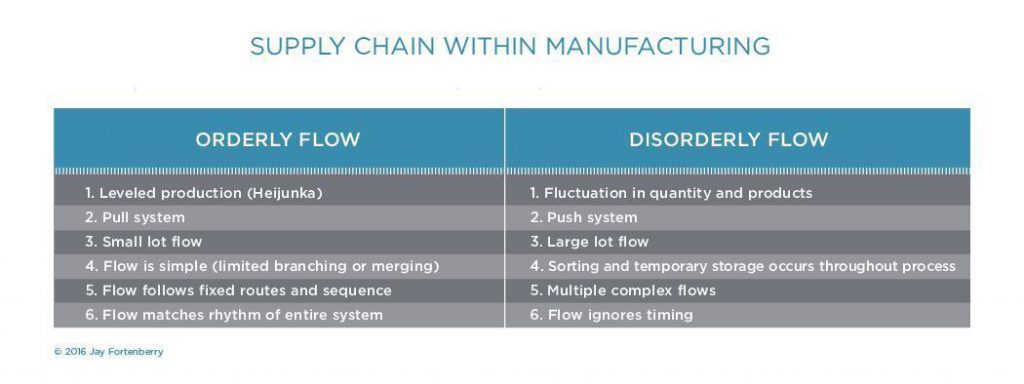

- Continuous Flow – or an orderly flow in the operations

- Takt Time – determining the pace of work by the required output in a certain working time

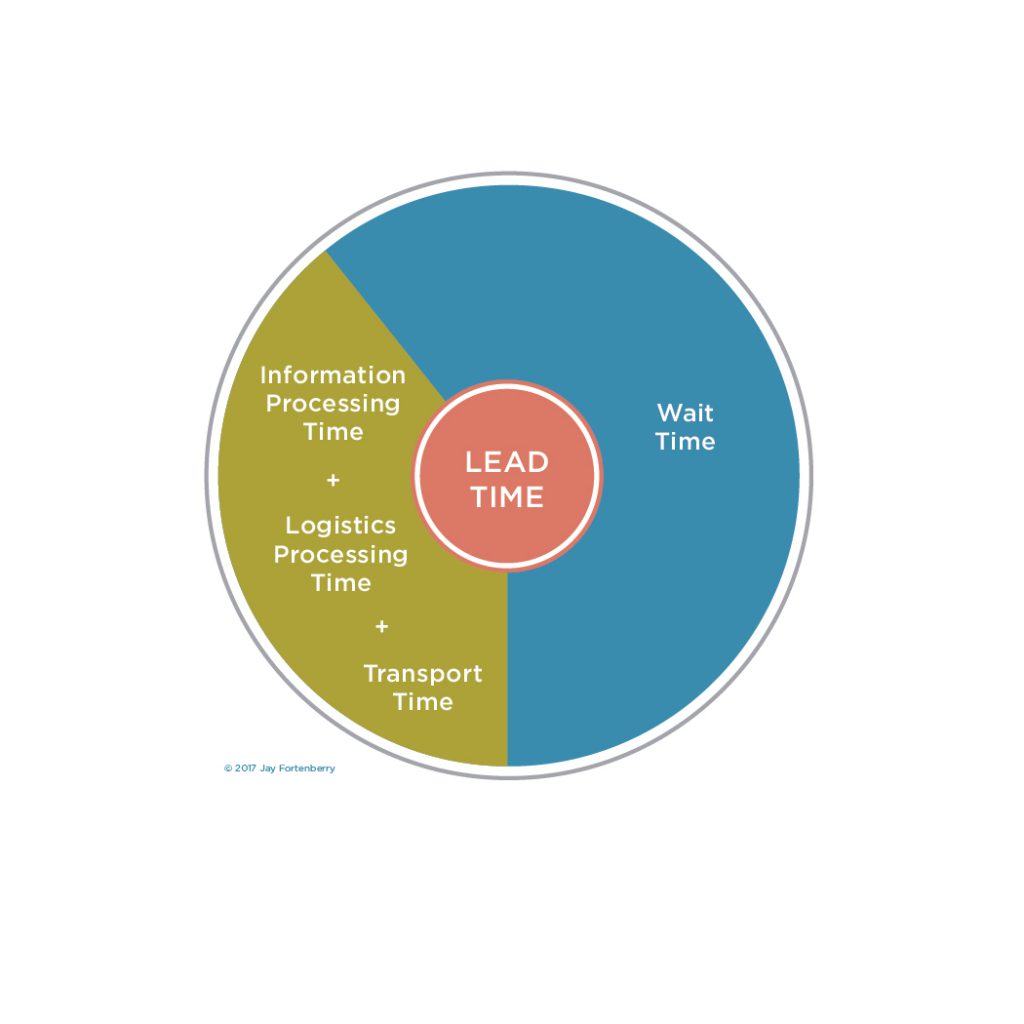

A basic precondition of Just in Time is Heijunka. Heijunka = Level production/ Level Flow, which is based on a well-planned schedule. The objective of Heijunka is to minimize lot size in order to increase the frequency to achieve level production – a mathematical equation.

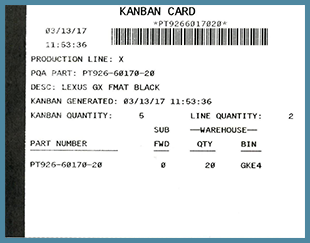

Kanban

Kanban is the cornerstone of TPS and the manifestation of on-the-job know-how. It is a signalling technique used to control the flow of materials, components or products from one operation to the next. It is also a system in which the following production process withdraws only the parts it needs, in the necessary quantity, when it needs them. Therefore, the preceding process only produces parts that will be consumed by the following process: this keeps a minimum inventory (or working capital).

Kanban is the cornerstone of TPS and the manifestation of on-the-job know-how. It is a signalling technique used to control the flow of materials, components or products from one operation to the next. It is also a system in which the following production process withdraws only the parts it needs, in the necessary quantity, when it needs them. Therefore, the preceding process only produces parts that will be consumed by the following process: this keeps a minimum inventory (or working capital).

The role of Kanban is to instruct the frequency and timing of delivery by providing:

- Instructions of production and conveyance

- A visual control to detect irregular process speed

- A tool to perform Kaizen (or continuous improvement)

When working a Pull System, each process responds autonomously to hour-by-hour/ minute-by-minute fluctuations so that the preceding process does not overproduce inventory. Additionally, when a problem occurs, the entire process stops, thus making the problem apparent to all.

Continuous Flow

Continuous flow processing is a system of production – now referred to as “one piece flow” – in which only one part is processed, then sent along the production line to the following process. This is based on a well-planned production schedule with the objective of minimizing lot size in order to attain the desired state.

Heijunka eliminates stagnation between processes in order to carry out one-piece flows. In production, stagnation makes up over 50% of the time, therefore, managing continuous flows aids in managing the time materials sit and sleep.

Takt Time

Takt Time is the time that should be taken to produce a product. This is based on the total operating time, with all machinery operating at 100% of working time.

Takt Time is achieved by performing standardized work for all processes. The end product of a standard work chart displays at each work station the outline of the operation for each worker. Additionally, this chart shows the essential work sequence, quality checks, and in-process stock for the task to be performed without Muda. Finally, standardized work shows the manual (as well as automatic) working and walking time at each location. This in turn is used to study the range that one worker can operate within the Takt Time to determine the most efficient way of executing the process.

Visual Control

Visual control is a method for supervisors to grasp at a glance whether the production activities are proceeding ‘normally’ or not. If there are problems, the supervisor must take action to remedy the problem immediately.

Andon is an electrical board which shows the current status of work to a supervisor, which enables countermeasures to be adopted quickly. A whiteboard at the workstation is also used to record the goals and actual production numbers, with problems recorded. A supervisor checks this board hourly to absorb the current status of their operation.

Jidoka

One of the basic premises of Toyota Production System is that defects are never to be passed on to the next work station. Jidoka = Humanized Automation, which builds quality into the process. When a machine detects an abnormality, it immediately stops and sends a warning to the person in charge. This prevents defective production, facilitates control of defects, promotes a safe working place and prevents over production.

Kaizen

Kaizen (or continuous improvement) is many baby steps that add up to great big steps. After arriving at Toyota I became fully immersed in the art of problem solving, and learned the recipe needed to:

- Develop a standard approach, but adapt and implement for each line of business

- Understand and analyze all of the components of a problem

- Pursue improvements based on effort and impact.

- Link improvements to performance

- Perform continuous improvement

Determining where a process starts and where it stops is critical to building a proper value stream map. Once identified, improvements for each of these areas can be translated into action plans. A completed Value Stream Map tells the story of a series of activities, identifies waste and opportunities to improve the end-to-end process. From here, the business can determine its best path forward for making improvements. Additional points to keep in mind are:

- Safety and quality are always preconditions

- Kaizen only comes from necessity

- The ideal condition is always pursued

- Genchi Gembets, Gemba, or Go and See are the watchwords of the day

- Find the root cause by using the 5 Whys

- Concept follows actions

- Kaizen requires speed rather than perfection

- Do work Kaizen rather than machine Kaizen

Seeing the problem firsthand allows the team to identify situations requiring improvement and to create a problem statement that describes the Who, What, When, Where and Why of a problem. With this grounding, problem solving becomes like forensic science, or a game.

Wrapping Up

Thousands of pages have been written on the Toyota Production System, with a whole cottage industry built to teach it. Having been witness to it, I’ve typically felt that many of these books, magazines, speeches and websites lacked the soul to provide a true understanding of how the TPS philosophy infused the organization: you really have to live the life.

Perfection is an interesting topic that means little until you actually have to do it. You have to live it relentlessly – there’s a motion about it that is simply impossible to describe. Still, the tools that make up the Toyota Production System are simple – in fact, a part of its genius is that there is nothing too complicated so that everyone can ‘get it.’

Toyota Production System is all about managing inventory while taking care of your employees and suppliers, and it works. Our Toyota suppliers would do things for us that they wouldn’t do for anyone else, all because we took care of them. It’s a lesson that I learned the right way, and that I’m teaching my students today.

I also carried it forward into my own Fortenberry Cash to Cash Method. TPS was designed to make full use of all of a business’s resources, from its facilities and machines to the capabilities of its workers. It taught that customer service was the mission and that the results were both a collective contribution to society and higher profits. By ensuring that the processes and tools are in place and motivating and training people, you are able to achieve remarkable things.